Tag: bp_docs_comment_access_anyone

Anaesthesia

Anesthesia or anaesthesia is a state of controlled temporary loss of awareness that is induced for medical purposes.

Local anaesthesia numbs a specific part of your body, while general anaesthesia suppresses central nervous system activity resulting in unconsciousness and a lack of sensation. Sometimes general anaesthesia is also referred to as “sleep medicine”. You may have to get this before a surgery or a test that may be painful or require you to sit or lay very still. Anesthesiologists (or “sleep doctors”) are experts in giving this type of medicine and monitoring your body so that you stay safe. They go to school for a very long time (about 12 years) to do this job.

There are two different methods of receiving general anaesthesia. One is through a mask (typically an option for children 9 and under) and the other is through an IV (preferred for most children 10 and up). –

- The mask is connected to a machine that blows anaesthetic gas onto your face, and the patient’s job is to sit or lay still and to breathe. After a little while of breathing in this gas, you will have that special sleep so you don’t hear, feel, or see anything during your procedure. The time it will take to fall asleep depends on your body, but it does take longer than getting an IV. The anaesthetic gas has a funny smell, kind of like a permanent marker.

- With an intravenous (IV), the anesthetic medicine goes straight into your bloodstream through a very small flexible tube. Your skin may feel cold as the medicine enters your body, but very soon after (around 5 seconds), you will have that special sleep so you don’t hear, feel, or see anything during your procedure. The anesthetic medicine is given throughout your entire procedure and once it’s over, it’s turned off. *See my post under the “procedures” folder in documents for detailed information about getting an IV.*

Shortly after the anesthetic is done being administered, you’ll wake up. You may feel a bit groggy and confused.

Read below to see the answers to some questions I asked an anesthesiologist:

- How do you decide between administering anaesthesia via mask vs. IVs for patients?

Most of the time, we always would prefer to use an IV to administer anesthetic. It is safer for patients. When children are younger sometimes they find starting an IV scary or upsetting so we will use a mask to put them to sleep first. As a general rule, we will put most kids to sleep with a mask 10 years and under if they prefer. Kids come in all sizes though. If you are over 100lbs no matter what your age, an IV is a safer way to go to sleep. There are other medical factors that may mean you need an IV anesthetic – medical conditions, airway structure, if you have recently had something to eat… Your anesthesiologist will let you know what is safe for you. Anesthetics are dosed by weight, so the bigger you are the more you need. It takes a lot of anesthetic gas to breath in when you are big. Anesthetic gases are quite stinky and I don’t like masks, so if I was going to sleep I would always choose an IV.

- So often people think “nothing to eat or drink after midnight” is what we want – NOT TRUE! Coming in dehydrated usually makes you have more nausea, makes it harder to start IVs and makes you hungrier as well. Follow the instructions left by your anesthesiologist – which may include a drink of clear fluids.

- Try and discuss the plan for induction of anesthesia beforehand. If you are using a mask, try practice breathing into a mask at home. If you are getting an IV think about how you want to distract yourself while it is happening. Do you need freezing cream before the IV? If there are specific things that really stress you (i.e. too many people, loud sounds, bright lights) us know that and we can try and avoid those stressors as you are going off to sleep.

- Probably the biggest thing is that its ok and completely normal to be nervous (everyone is) .. this isn’t something that you do everyday. We know that. I’d be more surprised if you weren’t nervous. Luckily this is something we do every day. We’ve spent a lot of time being an expert in putting people to sleep and waking them up safely – and you need to know that too. It will be ok.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

What is OCD?

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a mental illness. It’s made up of two parts: obsessions and compulsions. People may experience obsessions, compulsions, or both, and they cause a lot of distress.

Obsessions are unwanted and repetitive thoughts, urges, or images that don’t go away. They cause a lot of anxiety. For example, someone might worry about making people they love sick by bringing in germs. Obsessions can focus on anything. These obsessive thoughts can be uncomfortable. Obsessions aren’t thoughts that a person would normally focus on, and they are not about a person’s character. They are symptoms of an illness.

Compulsions are actions meant to reduce anxiety caused by obsessions. Compulsions may be behaviours like washing, cleaning, or ordering things in a certain way. Other actions are not obvious to others. For example, some people may count things or repeat phrases in their mind. Some people describe it as feeling like they have to do something until it feels ‘right.’ It’s important to understand that compulsions are a way to cope with obsessions. Someone who experiences OCD may experience distress if they can’t complete the compulsion.

People who experience OCD usually know that obsessions and compulsions don’t make sense, but they still feel like they can’t control them. Obsessions and compulsions can also change over time.

Who does it affect?

OCD can affect anyone. Researchers don’t know exactly what causes OCD, but there are likely many different factors involved, such as family history, biology, and life experiences.

What can I do about it?

Obsessive-compulsive disorder can be very challenging and hard to explain to other people. You may feel embarrassed, ashamed, or guilty. These feelings can make it hard to seek help. Because obsessions and compulsions take a lot of time, it can be hard to go about your daily life. Many people describe OCD as something that takes over their life, and this is not easy to deal with. But the good news is that OCD is treatable. It’s important to talk to a health professional.

Counselling and support

A type of therapy called cognitive-behavioural therapy (or ‘CBT’) is shown to be effective for helping people with OCD. It teaches you how your thoughts, feelings, and behaviours work together, and teaches skills like solving problems, managing stress, realistic thinking and relaxation. For OCD, therapy may also include a strategy called exposure and response prevention, which helps you learn new ways to look at obsessions and compulsions.

Support groups can also be very helpful. They are a good place to share your experiences, learn from others, and connect with people who understand what you’re going through. OCD can make people feel very isolated and alone, so support groups can be a good way to build a support network.

There are many self-help strategies to try at home. Small steps like eating well, exercising regularly, and practicing healthy sleep habits can really help. You can practice many CBT skills, like problem-solving and challenging anxious thoughts, on your own. Ask your support team about community organizations, websites, or books that teach CBT skills. And it’s always important to spend time on activities you enjoy and connect with loved ones.

Medication

Antidepressants are the most common medication for OCD.

How can I help a loved one?

Supporting a loved one who experiences OCD can be challenging. Many people feel like they have to follow along with a loved one’s compulsions. Some people who experience OCD avoid certain things or activities, and other people may feel like they have to do everyday things for a loved one.

You may have many different complicated feelings. You may feel upset when a loved one is experiencing distressing symptoms of OCD, but you may not see why a normal task could be a problem. You may want a loved one to be more independent, but see how challenging certain things can seem. If a loved one’s experiences with OCD affects others, especially young people, it’s a good idea to seek counselling for everyone. Family counselling is a good option for the entire family. Here are more tips to help you support someone you love:

- A loved one who experiences OCD usually understands that their experiences don’t make sense. Trying to argue with obsessions or compulsions doesn’t help anyone.

- Avoid ‘helping’ behaviours around OCD—for example, helping a loved one avoid things that cause anxiety. This can make it harder to practice healthy coping skills in the long run. Instead, it may be more helpful to focus on the feelings behind the behaviours.

- Signs of OCD can be more difficult to manage during times of stress—and even happy occasions can be stressful. Recognize that a loved one may need extra supports, and try to plan ahead.

- Every small step towards managing OCD behaviour can take a lot of courage and hard work, so celebrate every victory.

- Set your own boundaries, and seek extra support when you need it. Support groups for loved ones can be very helpful.

Phobias and Panic Disorders

Everyone feels scared at times, and it is a normal and good thing. But sometimes, fear becomes too much. This fear stops us from going about our usual routines or working towards our goals. Phobias and panic disorder are two examples of mental illnesses that can lead to these problems.

What are phobias?

A phobia is an intense fear of a specific thing like an object, animal, or situation. Two common phobias include heights and needles.

We all feel scared of certain things at times in our lives, but phobias are different. People change the way they live in order to avoid the feared object or situation. For example, many people feel nervous about flying, but they will still go on a plane if they need to. Someone who experiences a phobia around flying may not even go to an airport. Phobias can affect relationships, school, work or career opportunities, and daily activities.

What is panic disorder?

Panic disorder involves repeated and unexpected panic attacks. A panic attack is a feeling of intense fear or terror that lasts for a short period of time. It involves physical sensations like a racing heart, shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness, shaking, sweating or nausea. A panic attack goes away on its own.

Panic attacks can be a normal reaction to a stressful situation or a part of another mental illness. With panic disorder, panic attacks seem to happen for no reason. People who experience panic disorder fear more panic attacks and may worry that something bad will happen as a result of the panic attack. They may avoid places, sensations, or activities that remind them of a panic attack.

Some people avoid any situation where they can’t escape or find help. They may avoid public places or even avoid leaving their home. This is called agoraphobia.

Who do they affect?

Anyone can experience panic disorder or a phobia. No one knows exactly what causes phobias or panic disorder, but they are likely caused by a combination of life experiences, family history, and experiences of other physical or mental health problems.

What can I do about it?

Most people who experience problems with anxiety recognize that their fears are irrational but don’t think they can do anything to control them. The good news is that anxiety disorders are treatable. Recovery isn’t about eliminating anxiety. It’s about managing anxiety so you can live a fulfilling life.

Your doctor will look at all possible options to make sure that another medical problem isn’t behind your experiences.

Counselling and support

Counselling can be very helpful in managing anxiety, and it’s often the first treatment to try if you experience mild or moderate problems. Cognitive-behavioural therapy (or ‘CBT’) is shown to be effective for many anxiety problems. CBT teaches you how thoughts, feelings and behaviours all work together. Counselling for panic disorder and phobias, in particular, may also include exposure. Exposure slowly introduces feared things or situations.

Support groups may be a good way to share your experiences, learn from others, and connect with people who understand what you’re experiencing.

There are many self-help strategies to try at home. Small steps like eating well, exercising regularly, and practicing healthy sleep habits can really help. You can practice many CBT skills, like problem-solving and challenging anxious thoughts, on your own. Ask your support team about community organizations, websites, or books that teach CBT skills. And it’s always important to spend time on activities you enjoy and connect with loved ones.

Medication

Antianxiety medication may be helpful. Some types of antidepressants can help with anxiety, and they can be used for longer periods of time. Some people take medication until their anxiety is controlled enough to start counselling.

How can I help a loved one?

Many people who experience anxiety disorders like panic disorder or phobias can feel ashamed about their experiences. They may blame themselves or see their experiences as a problem with their personality rather than an illness. It’s important to recognize the courage it takes to talk about difficult problems.

Supporting a loved one in distress can be difficult, especially if you don’t fear the object or situation yourself. You may also be affected by a loved one’s anxiety. For example, some people seek constant reassurance from family and friends, or demand that they follow certain rules. These behaviours can lead to stress and conflict in relationships. But with the right tools and supports, people can manage anxiety well and go back to their usual activities. Here are some tips for supporting a loved one:

- Remember that thoughts and behaviours related to anxiety disorders are not personality traits.

- A loved one’s fears may seem unrealistic to you, but they are very real for your loved one. Instead of focusing on the thing or situation itself, if may be more helpful to focus on the anxious feelings that they cause. It may also help to think of times you have felt intense fear to empathize with how your loved one is feeling.

- People naturally want to protect a loved one, but ‘helping’ anxious behaviours (like taking care of everyday tasks that a loved one avoids) may make it harder for your loved one to practice new skills.

- If a loved one’s behaviours are affecting you or your family, it’s a good idea to seek family counselling. Counsellors can help with tools that support healthy relationships.

- Be patient—it takes time to learn and practice new skills. Take time to congratulate a loved when you see them using skills or taking steps forward.

- Set your own boundaries, and seek support for yourself if you need it. Support groups for loved ones can be a good place to connect with others and learn more.

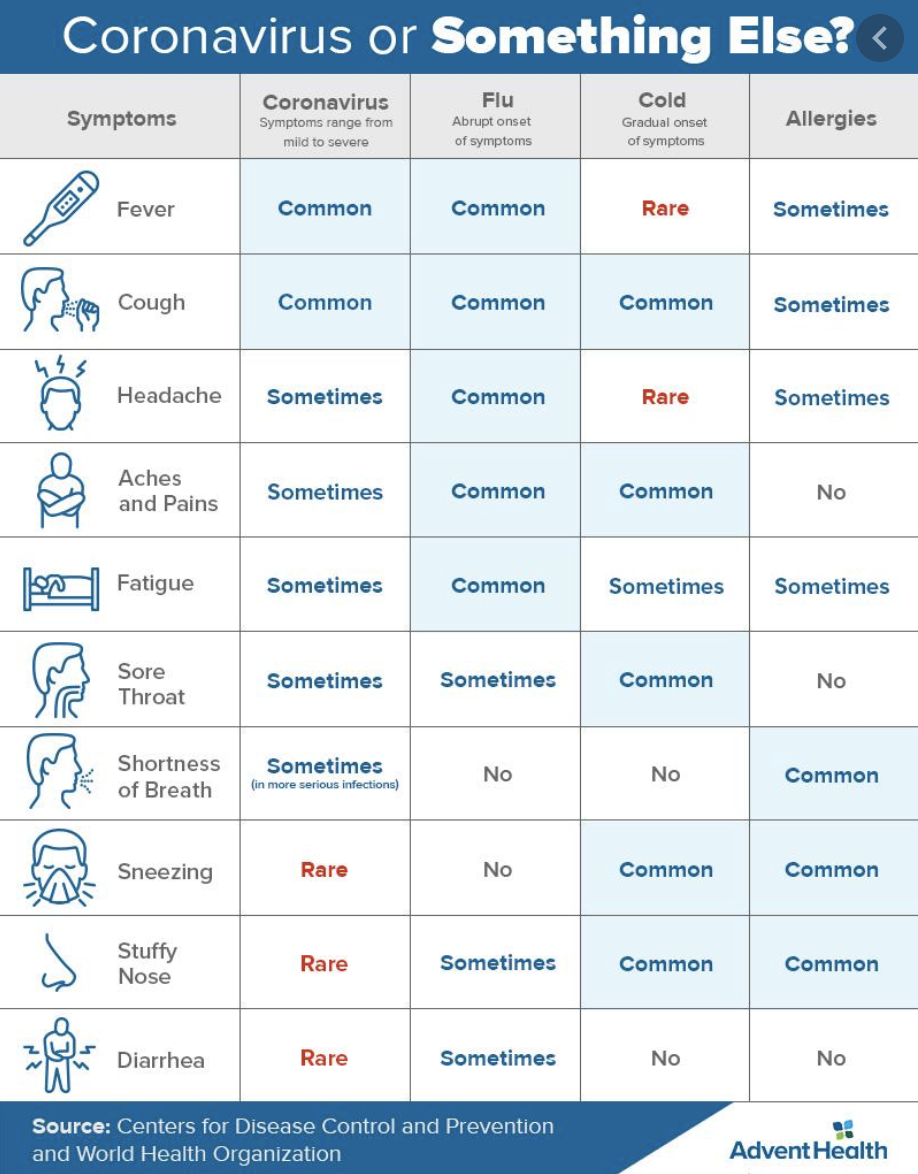

Coronavirus or Something Else? Symptom Comparison Chart

*This chart does not replace receiving a diagnosis or a test result, but is meant for you to assess your own symptoms if you’re unsure of what you may have.*

See more here: https://www.adventhealth.com/blog/coronavirus-vs-flu-or-common-cold-know-difference

What to do when you accidentally use the wrong pronouns

Last week we discussed gender pronouns, and how when someone shares their pronouns with you, you should try your best to remember what they are and use them appropriately. Of course, we’re all human, and sometimes mistakes happen. You may accidentally use “he” or “she” when referring to someone who’s told you they use “they” pronouns, for example. This is also called misgendering someone.

Consider these tips if you make a mistake:

1. When someone shares their pronouns with you, actively listen to what they are. Try to repeat them in your brain in a way that you will remember.

2. If you accidentally use the wrong pronouns when speaking about that person, calmly apologize, correct yourself, and continue speaking.

Do this even if they’re not around. This will help you to remember to use the right pronoun in the future, will help others to remember, and will communicate your allyship (support) to the LGBTQ2S+ community. There is no need to excessively apologize, justify why you made the mistake, or defend yourself. Doing this only centers your own needs and feelings over the persons who has been misgendered.

3. Commit to doing better. On your own time, take time to reflect on why you made that mistake and think about how you can prevent yourself from making it again. This may even involve practicing using pronouns you are less familiar with so you can be more confident using them in a sentence.

The general consensus is that if you misgender someone, it should never be the person who you misgendered’s responsibility to make you feel better about it or to help you do better at respecting their identity. Language can make such a huge impact on mental health and self-esteem, so we should all do what we can to communicate our respect to others with our words and reactions!

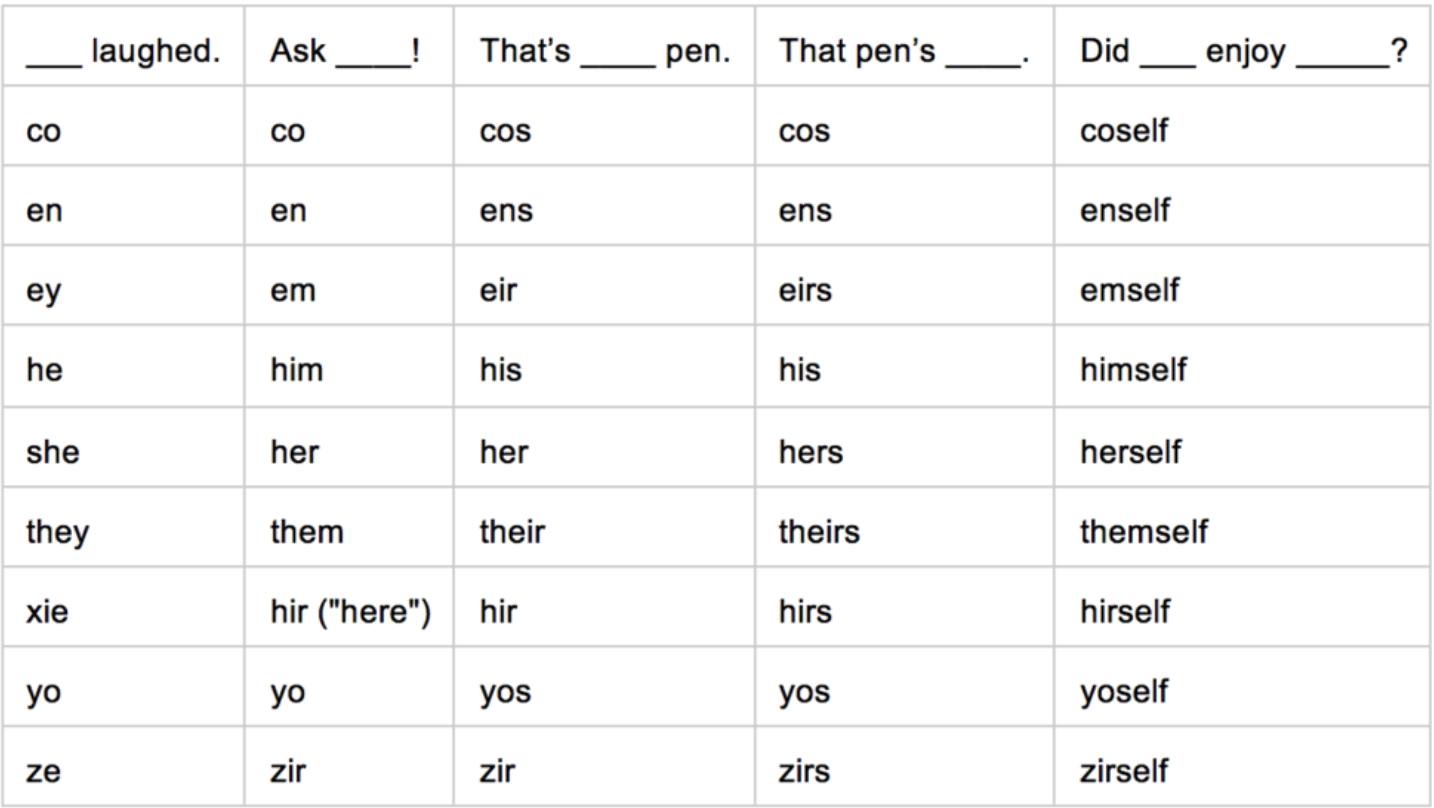

Gender pronouns

Gender pronouns are words someone would like others to use when talking about or referring to them. They are almost like a replacement in a sentence for your name. The most common pronouns used are “he, him, his” and “she, her, hers”. When someone is transgender or gender nonconforming, they may prefer to use different pronouns, such as “they, them, theirs”. There are many other pronouns someone may choose to use – check the graphic below to see what some of them are.

If you are cisgender, which means your gender identity matches the sex you were assigned at birth (i.e. born a female and gender identity is female), you may have not given much thought to pronouns before. People can typically guess what a cisgender person’s pronouns are by looking at them. Not everybody has this privilege! People who are transgender or gender nonconforming may use pronouns that you wouldn’t guess just by looking at them.

The pronouns a person uses are an important part of their identity. For people who are transgender, the shift in pronouns can be an important part of their transition. So, how can you be supportive? Stating your own gender pronouns and asking for other people’s gender pronouns when you meet them is a great way to communicate that you are supportive of all identities. Once someone tells you their gender pronouns, try your best to remember what they are and use them appropriately.

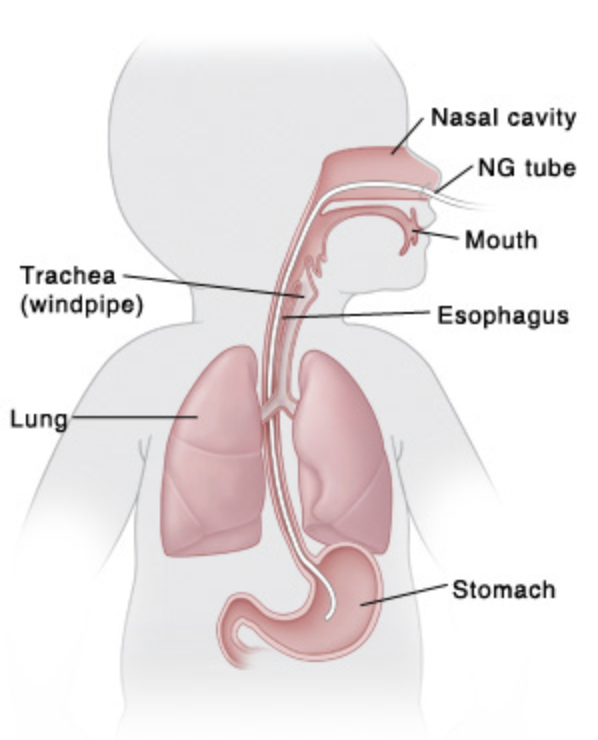

Tube Feeds

What is tube feeding?

Tube feeding can be a very effective therapy for people with irritable bowl disease. It can heal intestine damage, reduce swelling, make symptoms improve, and help you gain weight and height.

Tube feeding is a treatment that involves taking some or all of your daily nutrition in a liquid formula. In other words, it’s a way of giving your body the nutrition it needs. The doctors decide how much formula you must consume to stay healthy. Partial enteral nutrition (PEN) means you consume 30-50% of your calories from formula. Exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) means you receive all your calories from formula and do not eat regular meals. The formula enters your body through a tube, such as a nasogastric (NG) tube, which is a soft and flexible tube that goes from your nose into your stomach.

How does the tube get put in?

The tube is put in for the first time in the hospital, and this is where they teach you about what it is and how to continue them at home. Most kids say that having the tube put in is uncomfortable, but not painful. That uncomfy feeling starts to go away soon, too, as your body becomes used to having the tube there. It won’t be there forever.

Eating or drinking while tube feeding?

A lot of kids wonder if they can eat or drink anything while on tube feeds. This depends on your specific treatment plan and how much of your total calories you are consuming via the tube. Even when you are receiving all your calories from the formula (EEN), you may still be allowed to drink clear fluids or even chew gum. Ask your dietician what’s allowed for you and your body before trying anything at home ?

Here are a couple videos about feeding tubes:

Brief description of nutritional support & IBD: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6tbq_Lp7wnY

Getting an NG tube in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M2bbyFFVtnc

Vlog from a teen girl about adjusting to life with a feeding tube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUEL8yiEKEY

Valvular Stenosis

Anatomy of the Heart

The heart has four chambers. The two upper chambers are called the left and right atriums, and the two lower chambers are called the left and right ventricles. There is a valve at the exit of each chamber that ensures one-way continuous flow of blood through the heart.

The four valves are the tricuspid valve, pulmonary valve, mitral valve and aortic valve. These valves open and close to prevent blood from flowing backwards.

- Oxygen-poor blood coming into your heart from your body flows into the right atrium. The tricuspid valve is the valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle. It opens so blood can be pumped to the right ventricle.

- The pulmonary valve controls blood flow between the right ventricle and the lungs. It opens to let the heart pump blood out of the ventricles into the pulmonary artery toward the lungs so it can pick up oxygen. The oxygen-rich blood flows back from the lungs into the left atrium.

- The mitral valve lies between the left atrium and the left ventricle. It opens so the oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium can be pumped into the left ventricle.

- The aortic valve controls blood flow from the left ventricle into the aorta (the main artery in your body). When this valve opens, the oxygen-rich blood is pumped to the aorta and then out to fuel the rest of your body.

Stenosis

Stenosis is when the valve opening becomes narrow and restricts blood flow.

- Tricuspid valve stenosis: If your tricuspid valve narrows, blood is not able to fully move from the right atrium to the right ventricle. This can cause the atrium to enlarge, affecting pressure and blood flow in the surrounding chambers and veins. It can also cause the right ventricle to become smaller, so less blood circulates to your lungs to pick up oxygen.

- Pulmonary valve stenosis: If your pulmonary valve narrows, the flow of oxygen-poor blood from the right ventricle through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs is restricted. This affects your blood’s ability to pick up oxygen and deliver oxygen-rich blood to the rest of your body. With pulmonary valve stenosis, the right ventricle has to work harder to pump blood through the narrowed pulmonary valve and the pressure in the heart is often increased.

- Mitral valve stenosis: When the mitral valve narrows, blood flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle is reduced. This can cause fatigue and shortness of breath because the volume of blood carrying oxygen from the lungs is reduced. Pressure from the blood that has stayed in the left atrium can cause the atrium to enlarge and fluid to build up in the lungs.

- Aortic valve stenosis: When the aortic valve narrows, blood flow from your heart to your aorta (the main artery to your body) and onwards to the rest of your body is restricted. As a result, the left ventricle has to contract harder to try to push blood across the aortic valve. This can often lead to thickening of the left ventricle (left vernacular hypertrophy) which eventually makes the heart less efficient.

Causes

Valvular heart disease can develop before or at birth (congenital causes) or normal valves may become damaged during one’s lifetime (acquired causes). The cause of valvular heart disease is not always known.

Symptoms

Many people do not notice any symptoms until their blood flow has been significantly reduced by valvular heart disease. Symptoms can include:

- Chest discomfort, pressure or tightness (angina)

- Palpitations (irregular or rapid heartbeats caused by problems with the heart’s electrical system) can sometimes be a symptom of valvular heart disease. Your heart may be working harder.

- Shortness of breath – especially when you are active. Valvular heart disease reduces the amount of oxygen available to fuel your body and that causes breathlessness.

- Fatigue or weakness. You may find it harder to do routine activities such as walking or housework.

- Light-headedness, dizziness or near fainting (most common with aortic stenosis).

- Swelling can occur when valve problems cause blood to back up in other parts of the body, leading to fluid buildup and swollen abdomen, feet and ankles.

If you don’t have many symptoms or if they are mild and not affecting you too much, your doctor may choose to monitor your condition carefully and wait until it is necessary to treat your symptoms. It is important to understand that the symptoms of valvular heart disease may not necessarily reflect the seriousness of the problem. Regular check-ups are recommended.

Treatment

Treatment will depend on the severity of your disease! If it’s minor, you may not need treatment at all. You and your doctor will discuss your options based on your condition.

Options include:

- Medication: It cannot cure stenosis, but it may relieve the symptoms.

- Surgeries or other procedures: Such as valve repair or replacement.

- Lifestyle changes: Such as being smoke-free, active, a healthy weight, eating a balanced diet.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

What is post-traumatic stress disorder?

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental illness. It often involves exposure to trauma from single events that involve death or the threat of death or serious injury. PTSD may also be linked to ongoing emotional trauma, such as abuse in a relationship or having to undergo invasive or distressing medical procedures.

Something is traumatic when it is very frightening, overwhelming and causes a lot of distress. Trauma is often unexpected, and many people say that they felt powerless to stop or change the event. It could be an event or situation that you experience yourself or something that happens to others, including loved ones.

PTSD causes intrusive symptoms such as re-experiencing the traumatic event. Many people have vivid nightmares, flashbacks, or thoughts of the event that seem to come from nowhere. They often avoid things that remind them of the event—for example, someone who was hurt in a car crash might avoid driving.

PTSD can make people feel very nervous or ‘on edge’ all the time. Many feel startled very easily, have a hard time concentrating, feel irritable, or have problems sleeping well. They may often feel like something terrible is about to happen, even when they are safe. Some people feel very numb and detached. They may feel like things around them aren’t real, feel disconnected from their body or thoughts, or have a hard time feeling emotions.

People also experience a change in their thoughts and mood related to the traumatic event.

Who does it affect?

While most people experience trauma at some point in their life, not all traumatic experiences lead to PTSD. We aren’t sure why trauma causes PTSD in some people but not others, but it’s likely linked to many different factors. This includes the length of time the trauma lasted, the number of other traumatic experiences in a person’s life, their reaction to the event, and the kind of support they received after the event.

Some jobs or occupations put people in dangerous situations. Military personnel, first responders (police, firefighters, and paramedics), doctors, and nurses experience higher rates of PTSD than other professions.

What can I do about it?

Many people feel a lot of guilt or shame around PTSD because we’re often told that we should just get over difficult experiences. Others may feel embarrassed talking with others. Some people even feel like it’s somehow their own fault. Trauma is hurtful. If you experience problems in your life related to trauma, it’s important to take your feelings seriously and talk to a health care professional.

Counselling

A type of counselling called cognitive-behavioural therapy (or ‘CBT’) has been shown to be effective for PTSD. CBT teaches you how your thoughts, feelings, and behaviours work together and how to deal with problems and stress. You can also learn skills like relaxation and techniques to bring you back to the present. You can learn and practice many skills in CBT on your own. Exposure therapy, which can help you talk about your experience and reduce avoidance, may also help. It may be included in CBT or used on its own.

Medication

Medication, such as antianxiety medication or antidepressant medication, may help with anxiety itself, as well as related problems like depression or sleep difficulties.

Support groups

Support groups can also help. They are a place to share your own experiences and learn from others, and help you connect with people who understand what you’re going through. There may also be support groups for loved ones affected by PTSD.

How can I help a loved one?

When someone is diagnosed with PTSD, loved ones can also experience a lot of difficulties. You may feel guilty or angry about the trauma itself—then, on top of those feelings, experience difficulties around PTSD. You may feel like your loved one is a different person, worry that things will never be normal, or wonder what will happen in the future. Here are some tips to help you cope:

With support, people can recover from PTSD and the effects of trauma. Recovery is good for the entire family, especially for young people who are still learning how to interact with the world. A loved one’s recovery is a chance for everyone to learn the skills that support wellness.